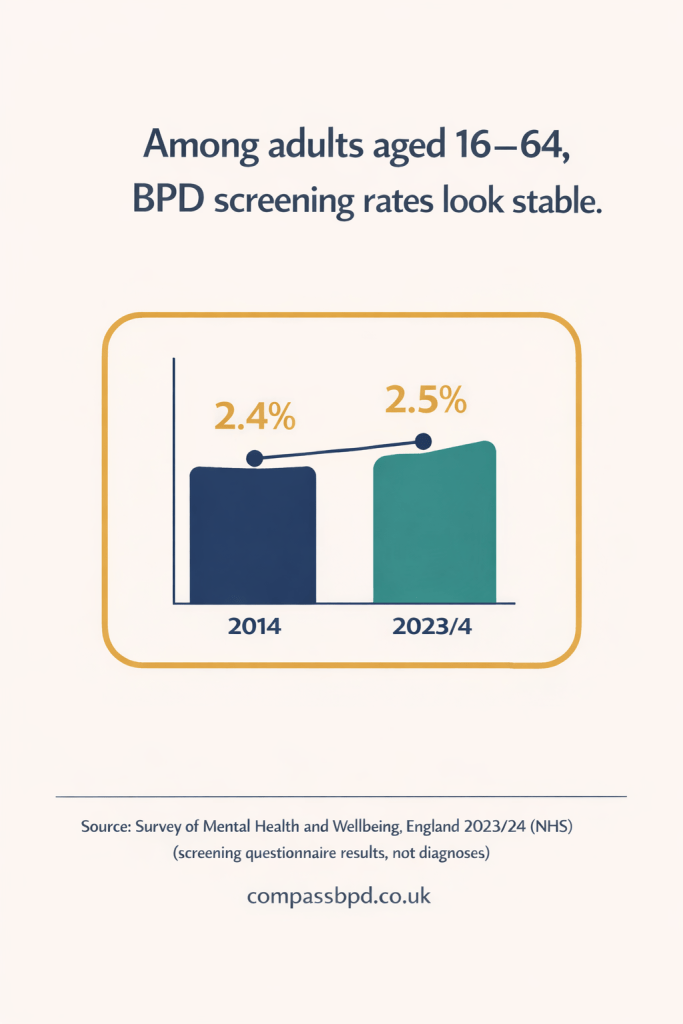

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) 2023/4 is a large NHS survey that gives a “snapshot” of adult mental health in England. It follows the same basic approach as the last APMS in 2014, so we can make some comparisons over time.

The survey results were published at the end of 2025.

This wasn’t an online poll. Researchers interviewed a random sample of adults in private households, and people answered the most sensitive questions privately on a laptop. Because it’s a household survey, it doesn’t include people living in settings like prisons or inpatient units, and it’s likely to under-represent people who aren’t in stable housing — all groups where mental illness rates are often higher.

This post focuses on what the survey suggests about Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

Boxes vs Spectrums

The report notes that personality disorder diagnosis is changing. Older systems tried to put people into categories (like “BPD”), even though many people don’t fit neatly into one box. Newer thinking treats personality disorder more like a spectrum: traits become a “disorder” when they’re so intense or inflexible that they seriously disrupt everyday life and relationships.

The APMS sits between the two approaches — it reports both category screens for BPD and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), and a broader screen for general personality disorder traits.

The report also notes a debate: critics worry a broad “general personality disorder” label could widen the net and increase stigma and pressure on services, while others argue personality disorder has been underdiagnosed and better recognition could improve care.

What Screened Positive Means

The APMS did not check people’s NHS records or diagnose them in clinic. It used questionnaires designed to work out if it’s likely someone has a condition like BPD.

So these figures do not mean a confirmed diagnosis after a full assessment — they mean screened positive on a questionnaire.

Key BPD Numbers

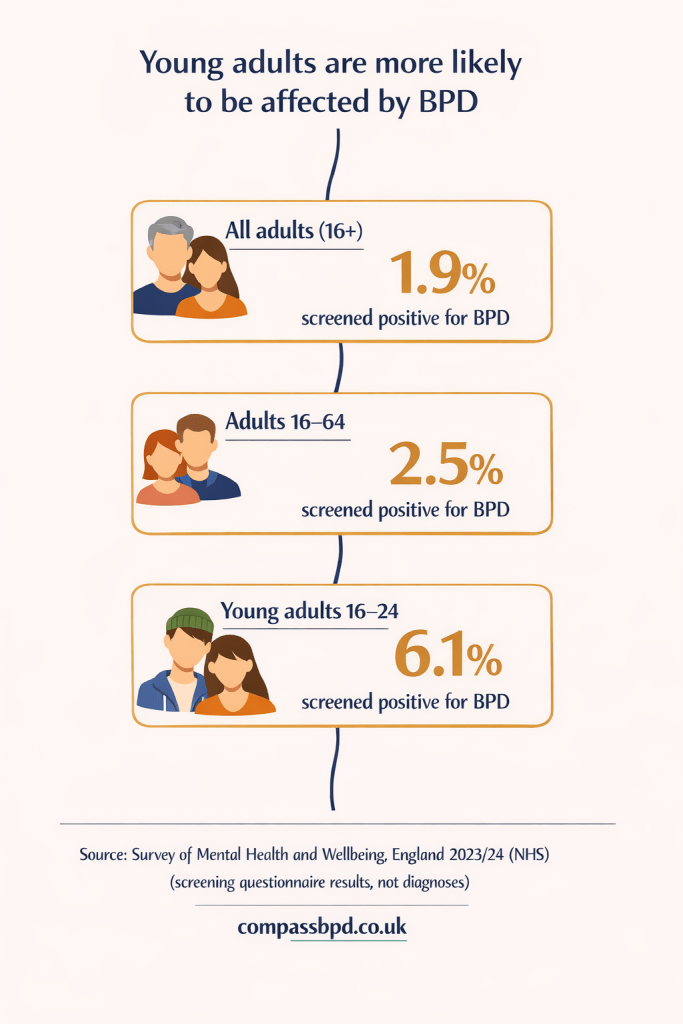

- We can compare data regarding numbers who screened positive for BPD with data from 2014

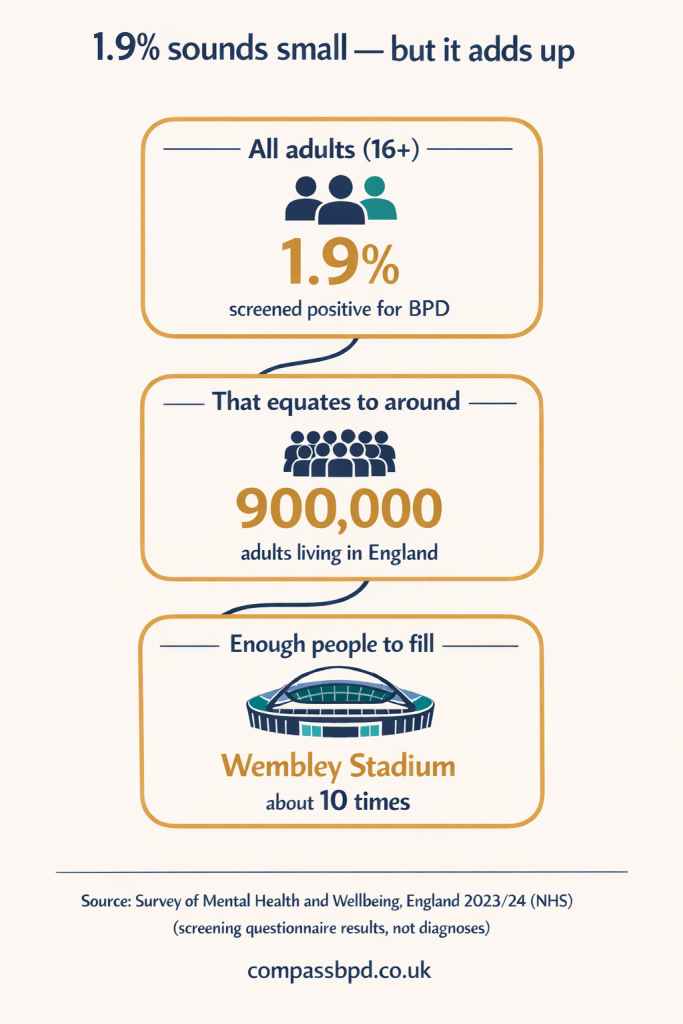

- If you look at all adults 16 years and older, 1.9% screened positive for BPD

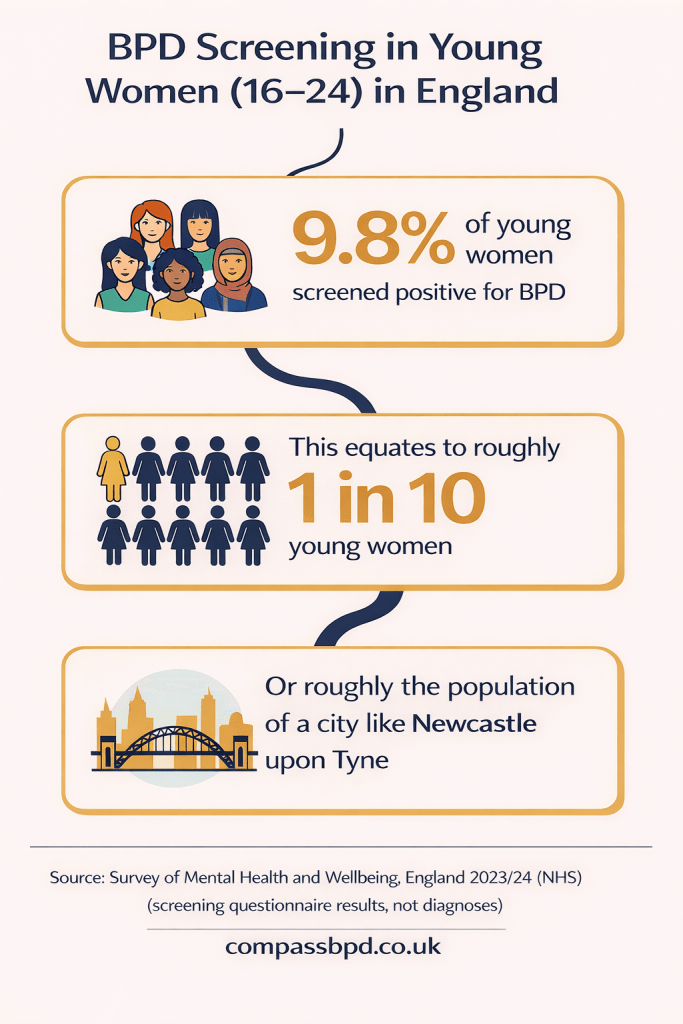

Young Women: A Standout Finding

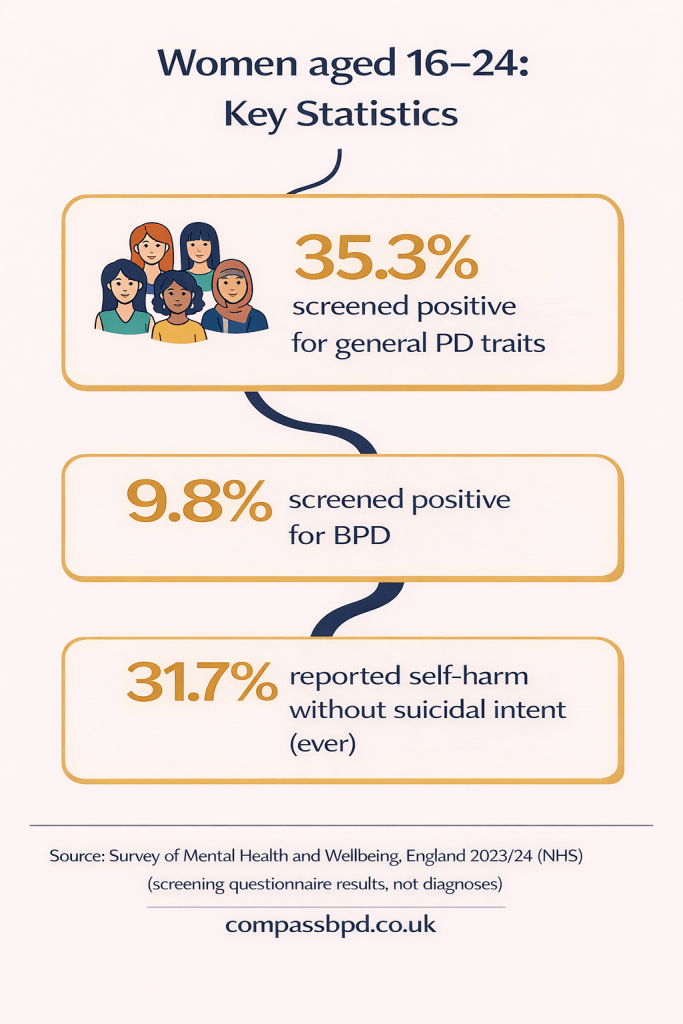

One of the most striking sets of results is for women aged 16–24. They suggest that young women are experiencing personality disorder and self-harm (a common feature of BPD) at among the highest rates in the survey.

The BPD statistic alone is cause for concern.

The report also notes that some critics see “personality disorder” labels as a way of medicalising understandable responses to trauma, inequality, and social pressure.

Are we diagnosing a biological disorder — or measuring the weight of modern society on young women?

A Big Caution: Overlap And “Diagnostic Overshadowing”

The report points out that BPD and general PD criteria can overlap with autism and complex PTSD, which can contribute to “diagnostic overshadowing” (thinking a symptom is linked to one condition when it’s really caused by a different one).

However, the report doesn’t publish a breakdown of any overlap between people who screened positive for BPD and autism or complex PTSD. Presumably because only 99 people in the survey screened positive for BPD, which limits how much detail you can reliably analyse.

For me, this is a key area of concern. How can the right treatment be given, if we don’t fully understand what is causing the behaviour?

The Soup Of Distress (What Tends To Cluster With PD Traits)

What the report does show clearly is that people screening positive for general personality disorder traits are more likely to be facing wider pressures — including unemployment and financial hardship, and higher rates of depression/anxiety and limiting physical health conditions.

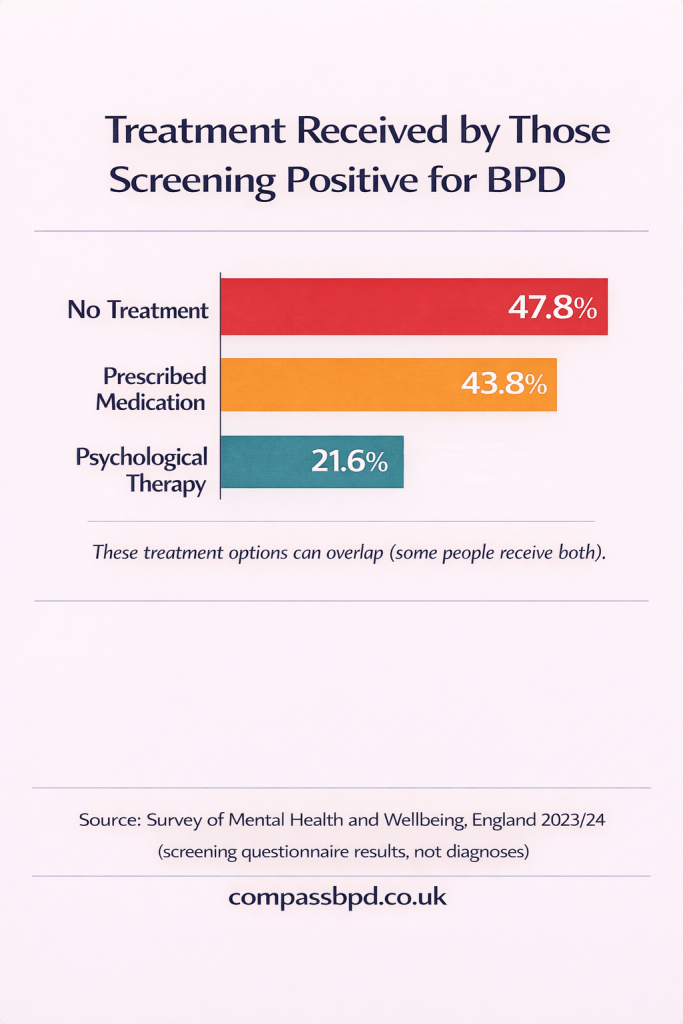

The Treatment Gap: Pills vs Therapy

The report suggests a mismatch between recommended care and what people report receiving.

The report concludes this points to a need to improve treatment and service provision (while also noting the small BPD sample size means we should be careful about over-interpreting).

One Hopeful Note – And One Hard Reality

A hopeful note is that the much lower screen-positive rates in older age groups challenge the idea that BPD symptoms must be lifelong for everyone (though the APMS can’t track individuals over time).

But the report also notes that this isn’t a trivial condition. It cites earlier UK research in people treated by specialist NHS mental health services (beyond GP care) where life expectancy was estimated around 18 years shorter than the general population, and notes many were likely to have had a BPD diagnosis.

Conclusions

My conclusion is that it’s great to have this big-picture overview of mental health in England — but the survey now raises questions that need much more granular research.

For example, my daughter has first-hand experience of diagnostic overshadowing: there are services for other conditions that won’t engage with her because she has a BPD diagnosis. That has been a major barrier to her getting better. The authors of this report suggest she isn’t the only one — but where is the data to confirm this pattern, measure its impact, and show what improves outcomes? Without clear evidence, it’s harder to push services to change.

The figure of around 1 in 10 young women screening positive for BPD is a wake-up call. Even allowing for the limits of screening tools, this is too common to ignore. It should trigger urgent research into what’s happening for young women — and why.

And the treatment picture won’t surprise anyone who has tried to access therapy for themselves or a loved one with BPD. It’s also not surprising that medication is used so often, even though there isn’t a drug that specifically treats BPD. When waiting lists are long and therapy is hard to access, people in crisis understandably want something — anything — that might ease their pain.

Now that this report is out, the question is: will we treat these findings as a headline, or as a prompt for real change — better data, better access to psychological help, and fewer people falling through the cracks?