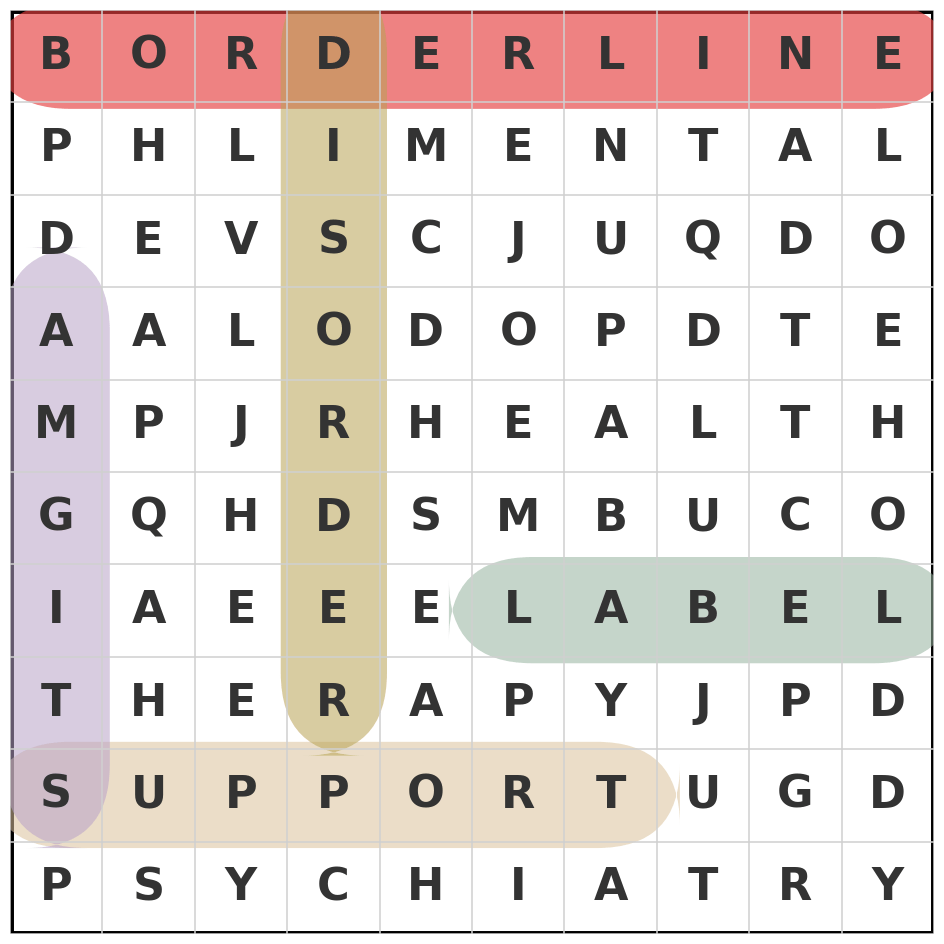

I keep thinking about a conversation we had earlier, dearest daughter. The one where I told you about the recent NHS survey suggesting that as many as 1 in 10 young women may have Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

I’m not sure how I was expecting you to react – I think I hoped it would make you feel less alone. But your initial reaction was disbelief. You pointed out that you don’t see hordes of young women having episodes out in public — and surely you would, if there were really 10% young women out there with the condition.

I got defensive

I’d spent so long looking at the report, trying to understand what it was saying, how the screening for BPD worked, that you refusing to believe it felt like you were saying my article was wrong — even though I was just reporting the results.

And I got that familiar feeling of frustration that has come from many years of me saying something and you automatically saying the opposite. Like disagreement is your reflex — even when I’m not arguing, just reporting.

Athough, in this instance, I think you have a point. One in ten young women potentially having BPD does seem impossibly high. But even it’s an overestimate and the real number is closer to one in twelve, or one in fifteen, that’s still a huge number of people.

Quiet suffering still counts?

Wanting to defend the statistic, I suggested that maybe some had a different, quieter form. After all, there are many different “flavours” of BPD — not everyone explodes in public.

You replied with your trademark bluntness: then they don’t really have a problem and shouldn’t count.

TikTok and self-diagnosis

You talked about TikTok and how frustrating you find it, seeing people doing posts, self-diagnosing themselves with serious mental health conditions like BPD — the “oh I get anxious and I wanted to kill myself once so I must have BPD” brigade.

I can see why this would irritate you. The not understanding. The seeming desire to jump on a bandwagon. The undeserving taking a slice of your pie.

But I also hate pecking orders of distress. The way people like to judge suffering and decide whether it is ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than an imaginary legion of others. It wouldn’t be so bad if these judgements were kept private, but they never are. People feel honour-bound to tell you your suffering isn’t as bad as someone else’s. You get put in your place — usually to shut you up.

I say this because it’s definitely not just you who judges, I do it — we all do. It has been part of society since forever. Perhaps it’s worse now because of social media. I don’t know. What I do know is that it needs to stop. There has to be another way.

A spectrum, not a tick box

I reflected on this new way of thinking about personality disorder — how it is now to be seen as a spectrum, not a tick box. This new framework may be more accurate but I fear it will turn people’s suffering into one long pecking order of distress.

Given that the NHS has limited resources, how will decisions be made as to whether you qualify for treatment for a personality disorder? How far down the continuum will you need to be? Will there be a magic algorithm that sifts through all the crisis team referrals and the hospitalisations and decides who is deserving? Not saying the system is any better now of course, but if the system is going to change, I’d like it to be for the better.

TikTok and your diagnosis

But then you talked about how TikTok was useful in your own journey to diagnosis.

You were at college and struggling and saw all these videos where people were describing what they felt and did. They called it BPD and you thought they meant bipolar. But when you looked up bipolar specifically, you thought: this isn’t me. So you were confused, and you talked to me about it.

I said BPD stands for Borderline Personality Disorder, not bipolar. That you having a BPD diagnosis was something I’d discussed with CAMHS a few years before, but they were reluctant to assess you at that age because emotional intensity and instability can look like ‘normal teenage’ stuff. But that maybe it was time to get you properly assessed – you were 19 at the time.

So I found a psychiatrist privately. Things were so bad I didn’t want to wait months or possibly years to find this out. And hey presto, we’d both been correct. Or rather, the psychiatrist agreed with us. She diagnosed you as having BPD.

Diluting the experience

The other thing you said that gave me pause: you refused to believe the 1 in 10 statistic because if it was true, it would give people an excuse to treat it as less serious. Like the volume somehow diluted the severity of experience.

And maybe what you were really reacting to wasn’t the statistic at all, but the risk that other people would use it against you. That they’d hear “mainstream” and translate it as: Not that bad. Not that urgent. Not worth resources.

Bandages

It made me think of the times we used to go to therapy after I adopted you. When we got ready for the journey home, you’d sometimes fake a fall and insist on bandages for an “injured” limb.

Even when we all knew what you were doing, you still needed it. Because pain that can’t be seen has a habit of being doubted.

Mental ill-health and trauma can feel brutally lonely for that reason: it’s invisible. And you found a clever way of making the invisible visible.

You’ve fought so hard to get me — and others — to understand how serious your pain is. So I can see why anything that hints your suffering is now commonplace might feel like it’s pushing you back into being unseen.

But what if….

… there are hundreds of thousands of young women like you out there — suffering and not being understood?

Maybe at the heart of this is a dialectical truth: you can be desperately unwell — and you can be one of many. Both things can be true at the same time.

If 1 in 10 young women do have BPD, that statistic doesn’t make it trivial. It makes it very, very urgent.