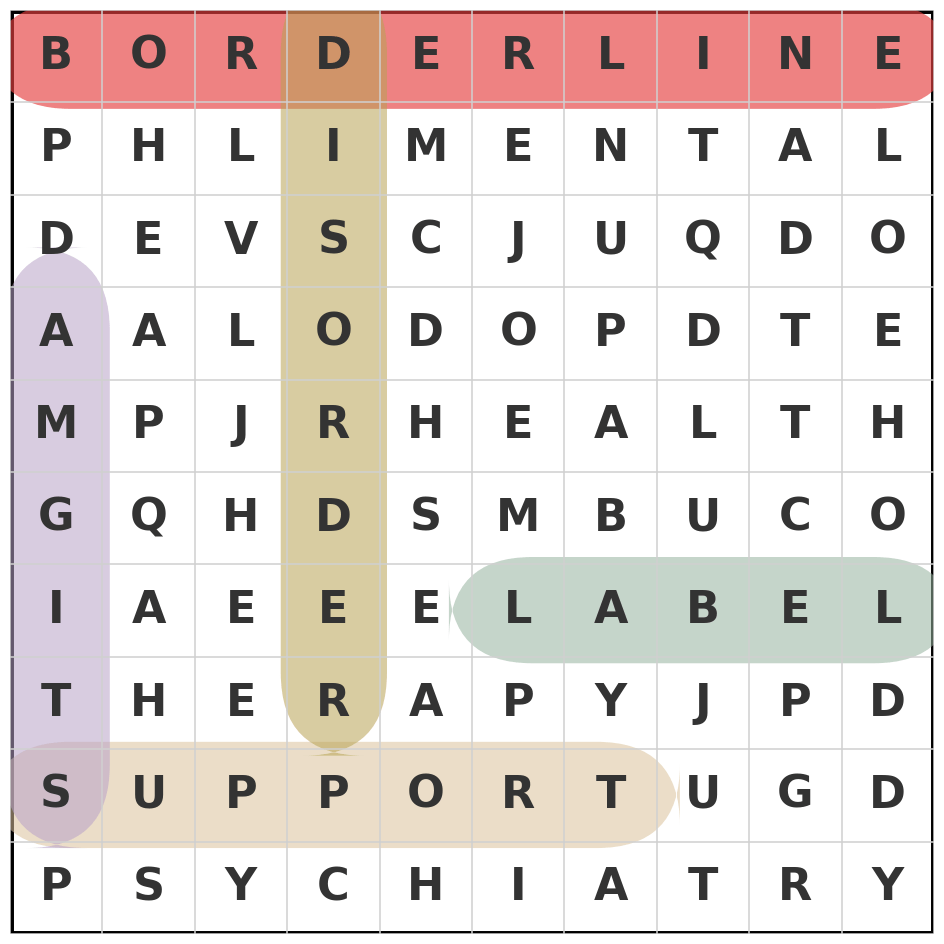

A look at how one of the most misunderstood mental health diagnoses ended up with multiple names and why the language we use still matters.

When I first started reading about BPD, I thought the name meant it wasn’t a very serious mental illness — that someone who had it was on the borderline of being mentally ill. Phew, I remember thinking, if that’s what my daughter has, it doesn’t sound too bad.

It soon became clear that it was, in fact, a serious and complex condition. And the confusion deepened when I realised that it’s also called Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder (EUPD) in some places. Other names cropped up too — Emotional Intensity Disorder, Emotional Dysregulation Disorder — leaving me wondering: Why does this one condition have so many different names?

A Bit of History

The term borderline was coined in 1938 by an American psychiatrist named Adolph Stern. He used it to describe patients he believed sat on the borderline between neurosis and psychosis.

At that time, mental illness was largely seen as falling into one of two camps:

- Psychosis — where people lost touch with reality, seeing or hearing things that weren’t real and often requiring hospital care.

- Neurosis — conditions such as anxiety or depression, which could be treated through psychoanalysis.

Stern realised he had patients who didn’t fit neatly into either category. When distressed, they could temporarily lose touch with reality, but most of the time they weren’t psychotic. They were highly anxious, emotionally volatile, but often didn’t respond well to traditional psychoanalytic therapy. These were the people he described as being on the borderline.

How Mental Illnesses are Classified

Agreeing on what to call diseases and symptoms has always been a challenge. The first International Classification of Diseases (ICD) was created in the 1890s to standardise how illnesses were recorded across countries.

Mental disorders were added in 1949, when the system came under the administration of the World Health Organization (WHO), which has managed it ever since.

A few years later, in 1952, the American Psychiatric Association produced its own manual — the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) — based on the ICD’s classification of mental illness. Over time, however, the DSM evolved into its own separate system.

Although both systems still cross-reference one another, they now differ in the way some conditions are described and named. This is the main reason why mental illnesses can end up with multiple names.

It’s also worth noting that while the DSM and ICD dominate psychiatric diagnosis globally, they’re not the only systems that exist. For example, China has its own manual — the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD).

A Bit More History – When Personality Disorders Entered the Picture

As psychiatry moved away from thinking about mental illness purely in terms of psychosis and neurosis, both the ICD and the DSM introduced a new group of conditions called Personality Disorders. These described long-term patterns of behaviour and emotion that caused significant distress or difficulties in relationships and daily life.

By the late 1960s, both manuals included a category for Emotionally Unstable Personality, but neither yet used the term borderline. Although it was being used out in the field – some influential psychiatric researchers had started repurposing this old psychoanalytic term and using it in their own work.

Over time, the two manuals developed their own versions of the diagnosis: the DSM settled on the name Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) in 1980, while the ICD updated its terminology in 1992 to Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, borderline type (EUPD).

So What is it Currently Called in the UK?

At the moment most UK clinicians still use the term Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder (EUPD) but this is changing.

The latest version of the International Classification of Diseases — ICD-11 — began rolling out internationally in 2022 and is gradually being adopted across the NHS. In this new version, the old term Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder (EUPD) has been replaced by “Personality Disorder,” rated by severity (mild, moderate, or severe) with an optional trait description.

This means the language in clinical notes will eventually shift from EUPD to something like:

“Personality Disorder, moderate severity, with borderline pattern.”

The transition to ICD-11 will take some time. It’s expected to replace ICD-10 in England over the next few years. Scotland has already begun using ICD-11 in some mental health settings, while Wales and Northern Ireland look like they are still in the planning stages.

No Wonder It’s Confusing

If you live in the UK, this can all feel like a right mess. If you go to your GP, they’ll probably use the term EUPD, because that’s the official language of ICD-10, still in use across most of the NHS.

Over the next few years, as ICD-11 is implemented, this will change — most likely to simply “Personality Disorder (borderline pattern)” — though no national guidance has yet been issued.

Meanwhile, my daughter calls it BPD, because that’s the term she sees on TikTok, where most of the content is made by American creators.

UK charities such as Mind currently try to bridge the gap by saying:

“Borderline personality disorder (BPD), also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD).”

Although this sort of description will presumably have to be updated now that the term EUPD is being phased out.

Adding to the confusion, you might also come across terms like Emotional Intensity Disorder or Emotional Dysregulation Disorder. These aren’t official diagnoses in either the DSM or the ICD, but they’re used informally by some clinicians, advocates, and people with lived experience who feel the phrase “personality disorder” is stigmatising.

The Problem with Personality Disorder

For many people, the term personality disorder itself is painful. It can sound as though there’s something wrong with their core self, rather than describing how trauma, neurodiversity, or emotional dysregulation affect them.

The name can also carry stigma and people often report feeling judged or dismissed once that label appears in their records.

The Problem with Borderline

It’s essentially a legacy label, a term that comes from a time when mental illness was understood very differently.

When the DSM formally introduced Borderline Personality Disorder in 1980, it kept the word borderline simply because it had already been informally used for decades — and no one could agree on a better name.

Today, it no longer refers to people being in a “borderline” state between anything. Now, clinicians use it as shorthand for a pattern of emotional and relational instability, but there’s nothing in the word itself that explains what it actually means.

Further Reading

If you’d like to explore more about how people feel about this diagnosis, I recommend the excellent report BPD Voices by CAPS Independent Advocacy.

It shares the wide range of feelings, experiences, and perspectives from people who have been diagnosed with BPD — including how they relate to (or reject) the label itself.

In Summary

The story of BPD/EUPD is as much about language and culture as it is about psychiatry.

The name has shifted across decades, continents, and classification systems — and so has our understanding of what it means.

As more people with lived experience help shape the conversation, perhaps we’ll see new ways to describe this condition that are less blaming, more accurate, and more compassionate.

However, given that both the DSM and ICD tend to evolve slowly and conservatively I’m not expecting an official name change any time soon.

Perhaps the best we can hope for in the short term is that a two-tier system gets created: one set of clinical terms used by professionals, and another set of names and descriptions used by people to explain their own experiences. Or will that just create even more confusion?

Sources and Further Reading

- Adolph Stern (1938) – Psychoanalytic Investigation of and Therapy in the Borderline Group of Neuroses, The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 7, 467–489. (Where the term “borderline” was first used to describe people seen as between neurosis and psychosis.)

- World Health Organization (2022) – ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision. (The global manual for all diseases, including mental health conditions. The ICD-11 now describes “Personality Disorder, with a borderline pattern.”)

- American Psychiatric Association (2022) – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm (Used mainly in the United States; describes Borderline Personality Disorder using nine diagnostic criteria.)

- NCBI Bookshelf – Borderline Personality Disorder Overview. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55415/ (Background on the historical and clinical understanding of BPD.)

- World Health Organization (1949–present) – History of the International Classification of Diseases.(The ICD first included mental disorders in 1949; it has been maintained by the WHO since then.)

- Royal College of Psychiatrists (UK) – Information on BPD and EUPD. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/mental-illnesses-and-mental-health-problems/personality-disorders/borderline-personality-disorder (how UK clinicians use both names)

- Mind (UK) – Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), also known as Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder (EUPD). https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/borderline-personality-disorder-bpd/

- CAPS Independent Advocacy (2022) – BPD Voices report (PDF). https://capsadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/BPD-Voices-final.pdf (Lived-experience perspectives on diagnosis, treatment, and the label itself.

- BMC Psychiatry – Application of the ICD-11 classification of personality disorders.https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-018-1908-3 (Explains how ICD-11’s new dimensional model replaced the older EUPD category.)